LANGUAGE EXPLAINED

Or how language can be regular and flexible at the same time.

There is a lot of confusion around what linguists do when they study languages. The first question that comes to everyone’s mind is: What is the purpose of studying languages if not to learn how to speak them?

The purpose of linguistics

The simplest answer to this is that we linguists look for regularities in a language — basically anything that behaves systematically and can be examined through the scientific method.

Grammar is a system of naturally occurring regularities in any language that we can all recognize. But other parts of languages, such as lexicon (vocabulary), also have their own regularities, however subtle they might be.

That said, the actual scientific purpose of linguistics is often murky. Just like in other humanities, we too feel the existential dread and the apparent lack of practical application of our discipline. But, fortunately for us, the importance of linguistics has never been more evident than it is today.

From the use of linguistic knowledge in Natural Language Processing (NLP) and AI to the critical need to support multilingualism and endangered languages, linguistics stands at the forefront of some of the major challenges of our time.

So, where do we go from here? Should you become a computer scientist working with NLP and/or an activist supporting multilingualism? Maybe, but maybe also consider taking a step back and join me in understanding how language works in the first place. Why is it so hard for computer scientists to crack this complex system? How is language conditioned by its environment and social/political pressures? And why is it so important as a marker of social identity?

The paradox of language

Let us indulge in this step back and start with a few basic but surprising properties of language. The study of language is all about paradoxes, at least in my opinion.* Whenever you find one rule by which languages operate, you will probably find another that does just the opposite. It is all about the balance of these different forces working together.

*Linguists tend to disagree just about anything. Keep in mind that this is my informed opinion as a scholar who likes to think she is an open-minded person.

What forces are these? First of all, language is a very regular system, with all its tenses, person inflections, maybe even cases. No matter the form, whether it is a particle or a suffix (the ending of the word), all languages will have a grammatical system to express at least some of these meanings.

For instance, in Nafsan, an Oceanic language spoken in a Pacific nation called Vanuatu, has a whole system of different person particles that come before the verb. They refer to different persons, as in first, second, third person singular, plural, and dual. This is similar to many Indo-European languages, although they usually do this through verb endings, as in “yo corro” (I run), but “ella corre” (she runs) in Spanish.

If I want to say “I went” in Nafsan, I would say “a pan”, where “a” means “I” and “pan” means “go”. But if I want to say “the two of them went” I need to say “ra pan”. Linguists say that “ra” refers to third person dual because it means “the two of them”. Dual is a relatively rare category in comparison to the widespread categories of singular and plural.

But language is also quite flexible. The particle or the suffix you use today to refer to, say, present tense might have sounded quite different a hundred or a few hundred years ago. One famous example is how “thou hast” from the Shakespearean times has changed to “you have”. Both the pronoun “thou” and the verb ending in “hast”, referring to second person singular, have changed over time.

Another way in which language is flexible is that we invent new words and new meanings all the time — you might even invent special words when you are with your family and closest friends. This is you being creative with your language use.

When enough people start using a certain new word, its spread means that the language is changing. Just think about how slang words change in less than 5 years — I know, it makes you feel old quite fast. I experienced this firsthand when I said “weed” in Croatian to my younger sister, who thought that the word I used was the lamest old people’s word she has ever heard. She is 7 years younger to be fair.

“I can say whatever I want”: Just how flexible is language?

You see how these are conflicting linguistic forces? Languages are simultaneously regular and flexible. I often hear from non-linguists that “of course language is flexible, you can say whatever you want”. That’s not quite true.

For example, in English I cannot say “I present gave him”. If you are a native speaker of English, you know this not because you learned it in school, but because you learned the English grammatical system organically as a child learning to speak.

This grammatical system, as abstract as it sounds, is just a collection of rules about how words combine, what they mean etc., and crucially the whole community of people who speak this language know these rules tacitly. That is, they agree on these rules by virtue of having learned the common language. That is why you can’t just break the rule of putting the English verb in the second place and expect people will just adapt to your new word order and start doing the same.

This is true for all languages. The rule of thumb here is that if a sentence sounds good to you (as a native or close-to-native speaker) it is grammatical, which means correct in linguistic terms. The grammatical rules you learn in school are just a social norm, which is a whole other issue we will discuss some other time.

On the other hand, the flexibility of language allows for sentences that used to be grammatically impossible to become possible. For example, in varieties of English like African American Vernacular, we can say “she run” when we mean “she runs”. In this case, the rule of adding -s in the present tense for third person singular in English became flexible and now allows a new form of the verb with the same meaning of the present tense.

However, this change happened over time for a multitude of reasons (see Winford, 2015) and wasn’t just a quirk of one speaker trying to change the language consciously. Under certain circumstances, this rule just happened to become more flexible for the whole community of speakers, who now agree on it and understand its new meaning.

Conclusion

I like to keep it short and sweet, so I will stop here, giving you the space to think about the conflicting nature of the rigid regularity and the flaky flexibility of language.

In upcoming articles in this publication, I will address some of the other conflicting “linguistic forces” and dive deeper into how language changes over time. Until then, let me know what you think about this contrast between regularity and flexibility. Would you agree with me that these are probably the two most basic “linguistic forces” that shape language?

Don’t forget to join our “Language Explained” newsletter!

And if you are a linguist and wish to contribute, get in touch!

Sources

Krajinović, Ana. 2020. Tense, mood, and aspect expressions in Nafsan (South Efate) from a typological perspective: The perfect aspect and the realis/irrealis mood. PhD thesis from Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and University of Melbourne. http://hdl.handle.net/11343/237469.

Thieberger, Nicholas. 2006. A grammar of South Efate: An Oceanic language of Vanuatu. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Winford, Donald, 2015. The origins of African American Vernacular English: Beginnings. In: Bloomquist, Jennifer, Lisa J. Green, and Sonja L. Lanehart (eds.). The Oxford handbook of African American language, p.85. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199795390.013.5

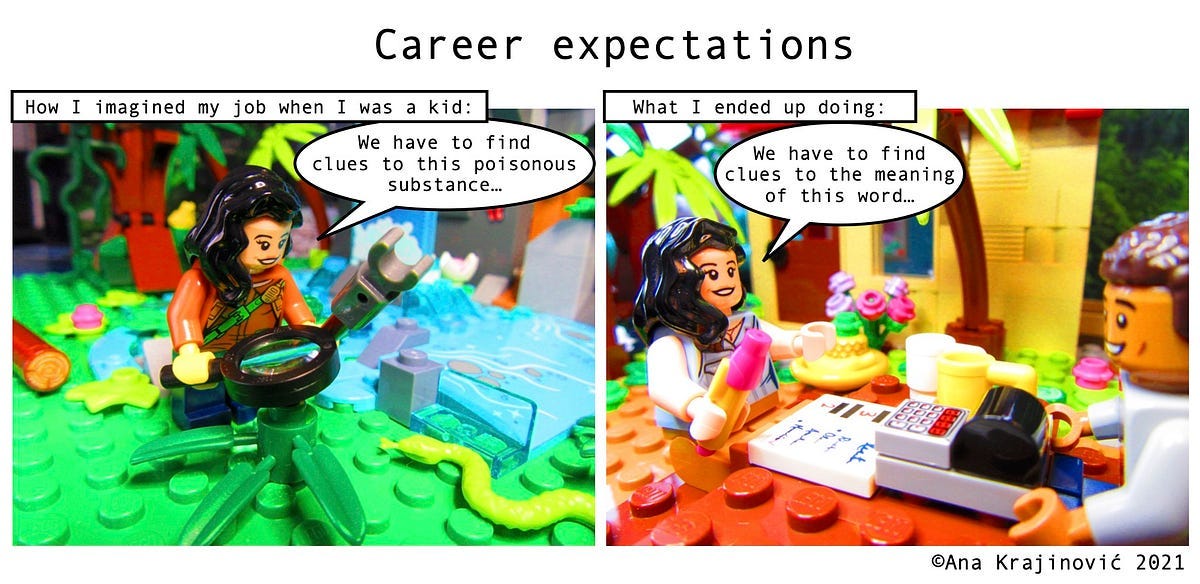

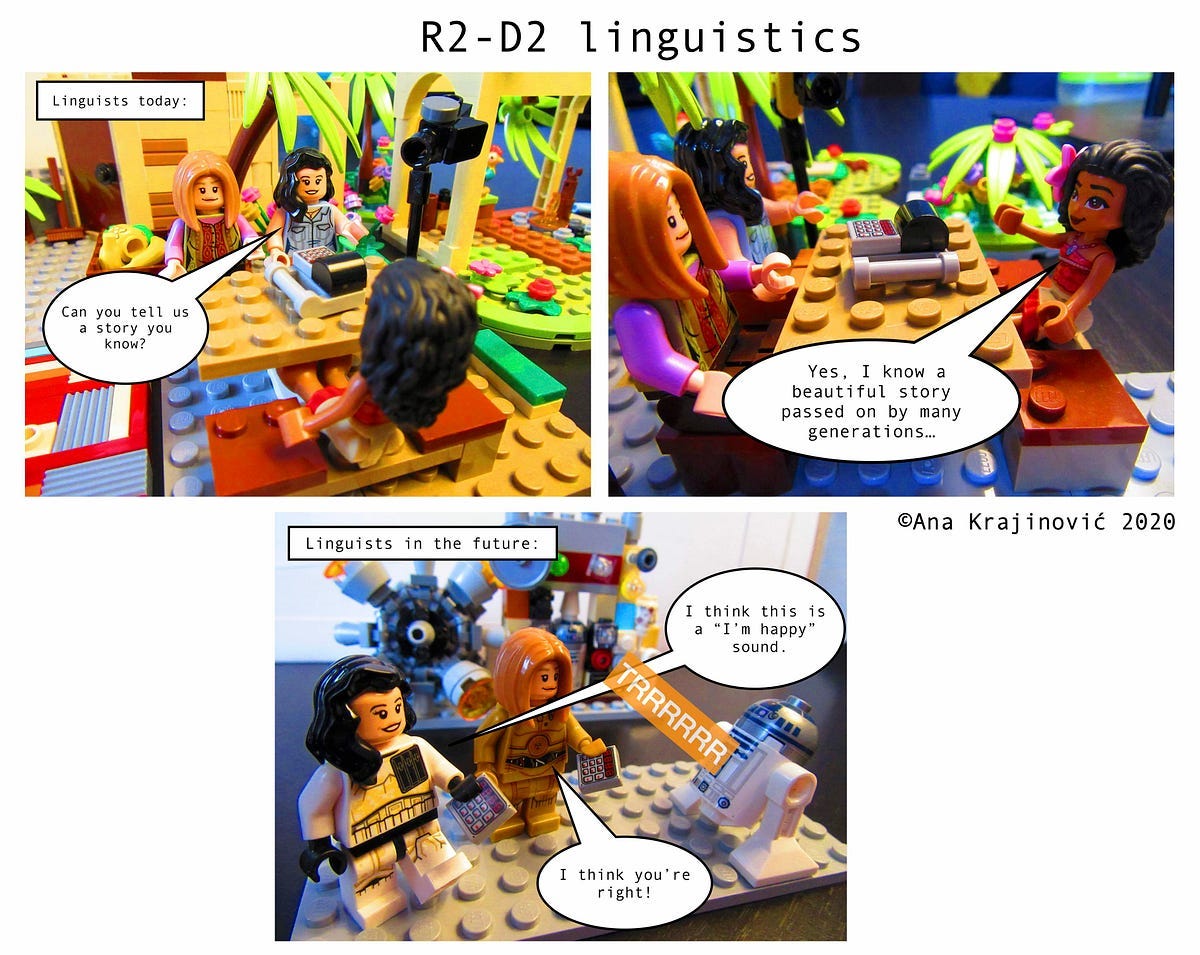

About the author and editor: Ana Krajinović

I am a postdoctoral researcher at the Heinrich Heine University of Düsseldorf. In 2020 I completed my PhD in linguistics at Humboldt University of Berlin and the University of Melbourne. I work on fieldwork-based semantics of Nafsan, an Oceanic language spoken in Vanuatu. During the pandemic, I started creating short comic strips about linguistics and fieldwork. My website: https://anakrajinovic.com.