Research on Comics Reveals How We Perceive What Is Alive

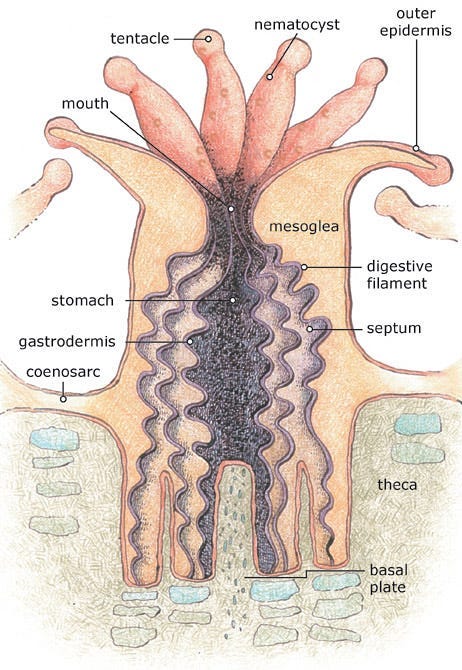

I know corals are alive, but they really don’t look like it.

Dear readers,

This week I have something different for you, an insiders look into my research on comics! (If you are a member on Medium, read the article here to support me, thank you!)

Have you ever wondered why we find it so hard to recognize that corals are alive, but we have such an easy time recognizing other animals?

This is the question I asked myself a few years back when I was snorkeling in Vanuatu. In fact, I was so dumbstruck by it that I kept looking at one of the corals for any sign of life.

You might say that you already know the answer to the question above. Corals don’t move, they don’t express themselves, they don’t seem to do anything other animals do, or at least they are too small for any of those activities to be visible to us. And you would be completely right. We do not pay attention to things that don’t visibly move. But why is that?

It is because of something researchers call “animacy preference”. Humans indiscriminately focus their attention on beings perceived as alive and sentient or “animate”. Everything else is a bit more like a background to our perception. If you had to describe the picture above in one sentence, how would you do it?

Try first before reading the next paragraph.

Did you first mention the diver or the coral? It is likely you mentioned the diver first, even though the coral is bigger and in the foreground. In our eyes, the coral is a part of the landscape and not a live entity, which makes it infinitely less interesting than a human. (This is instinctively and evolutionarily speaking, of course, it’s ok if you find corals more interesting.) In our evolutionary past, other humans and animals posed much more of a threat to our survival, so we learned to pay more attention to them (New et al., 2007).

But what is it about animates that draws our attention? Is it all about movement or something else?

If a coral could move like a rabbit does, we would make no mistake about it being alive for sure. But then again, inanimate things often move anyway, like clouds in the sky or a leaf taken by wind or water, so movement alone doesn’t really tell us much about whether something is animate or not. This question also plagued psychologists who ran several experiments on the perception of animacy (Opfer, 2002). What they found is fascinating.

In an experiment, they found that if a random-looking blob* is moving aimlessly, we (or the participants in the experiment) perceive it as inanimate. But if the blob moves toward a goal, in an intentional-looking manner, we perceive it as alive and sentient. Opfer’s (2002) conclusion is that goal-directed movement is the main indicator of animacy.

*A blob was chosen instead of a real animal so that the visual cues typical of animates, like posture, do not influence the results.

Comics

Together with my colleagues Neil Cohn and Irmak Hacımusaoğlu at Tilburg University, we decided to test Opfer’s conclusions on comics, because there artists can visually depict the goal-directed movement with lines. If humans perceive only the goal-directed motion as animate, we hypothesize that they will depict the motion of animates and inanimates differently. But in what way? Let us find out.

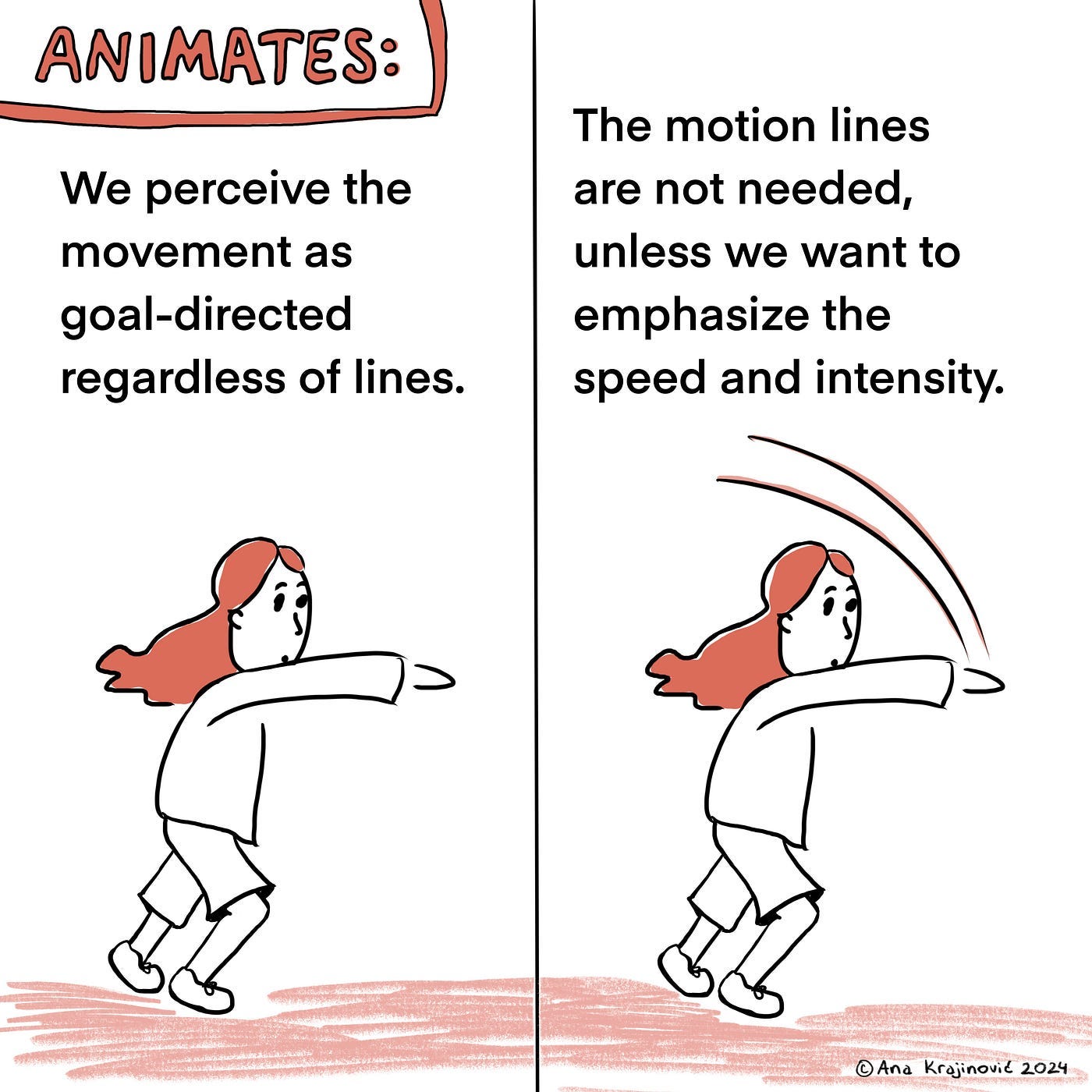

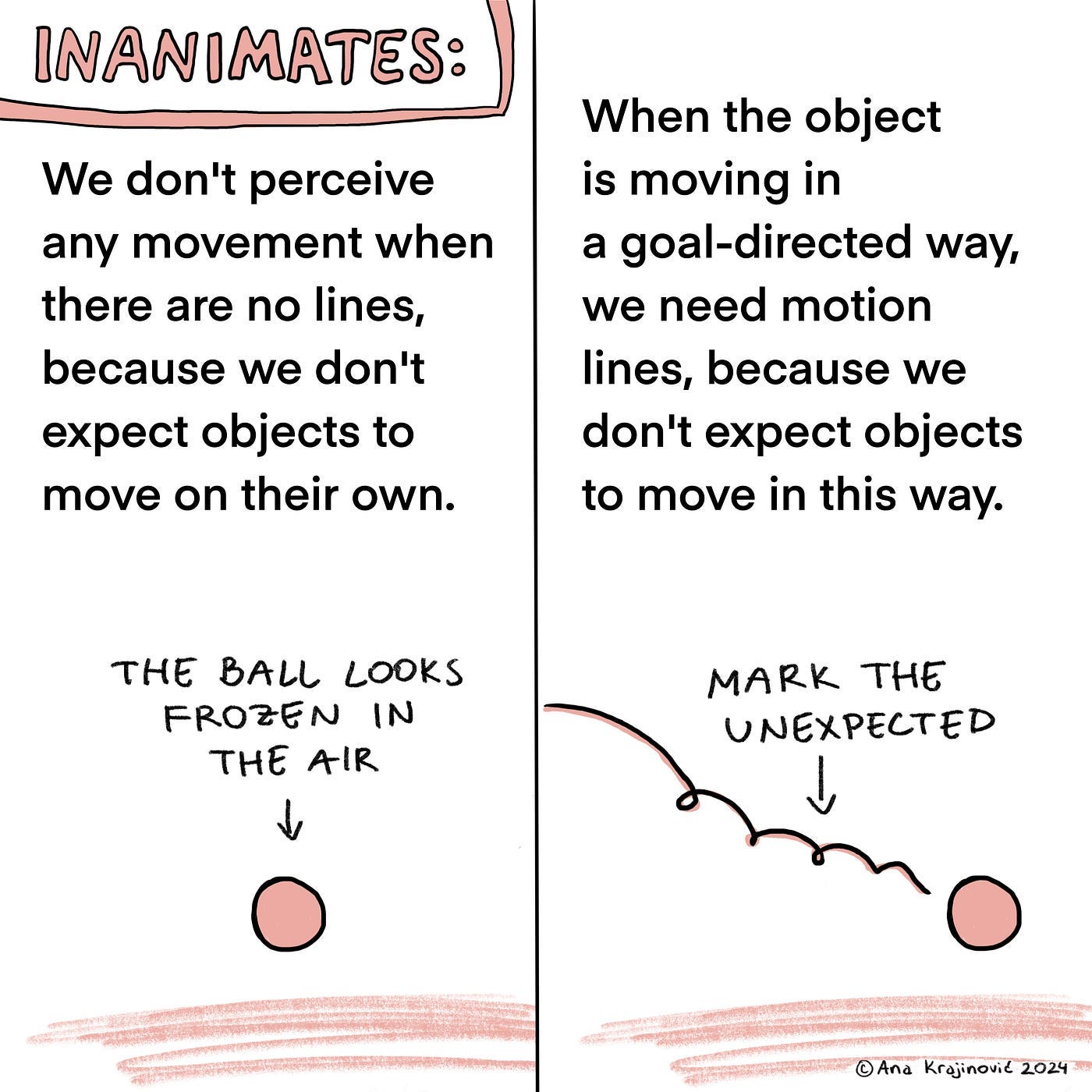

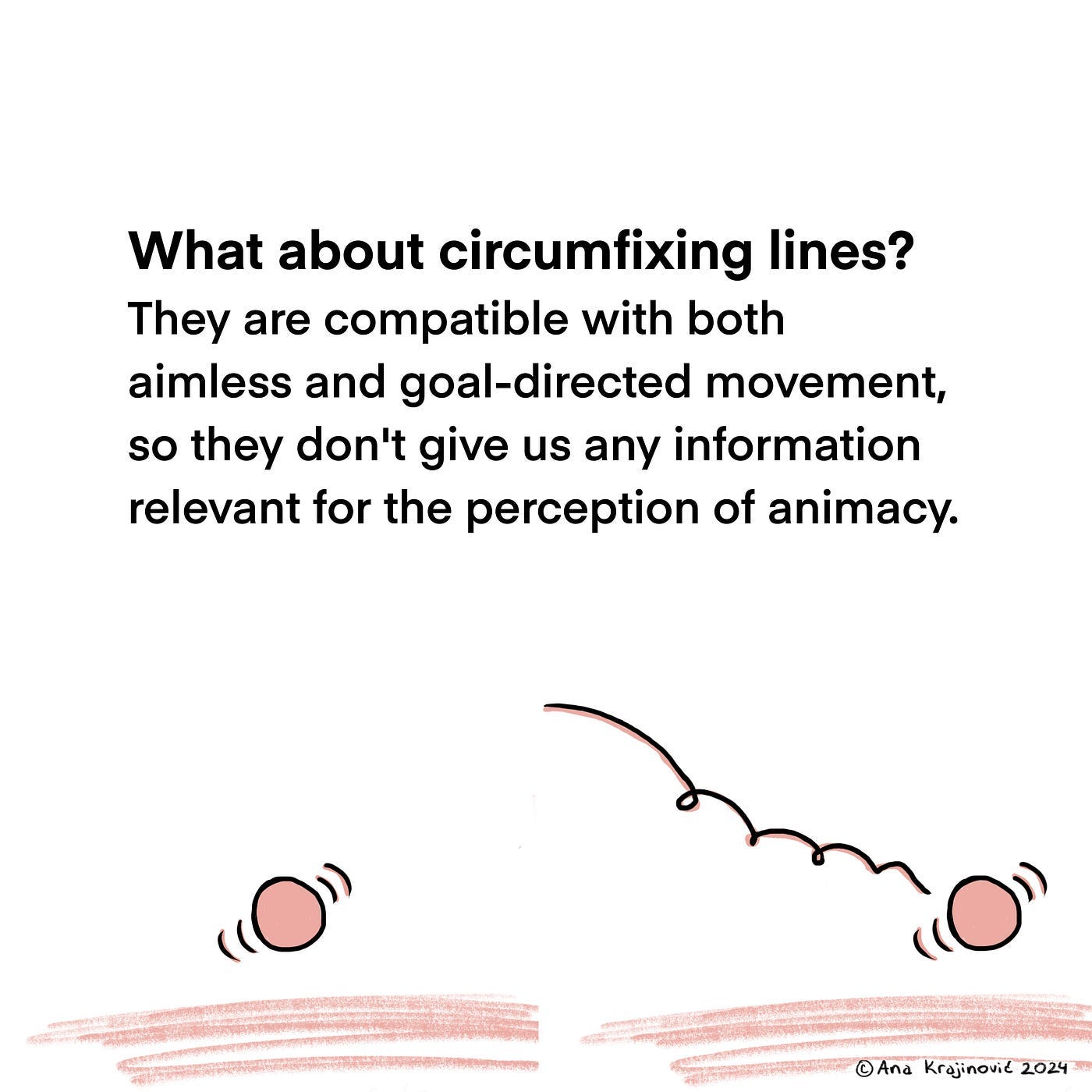

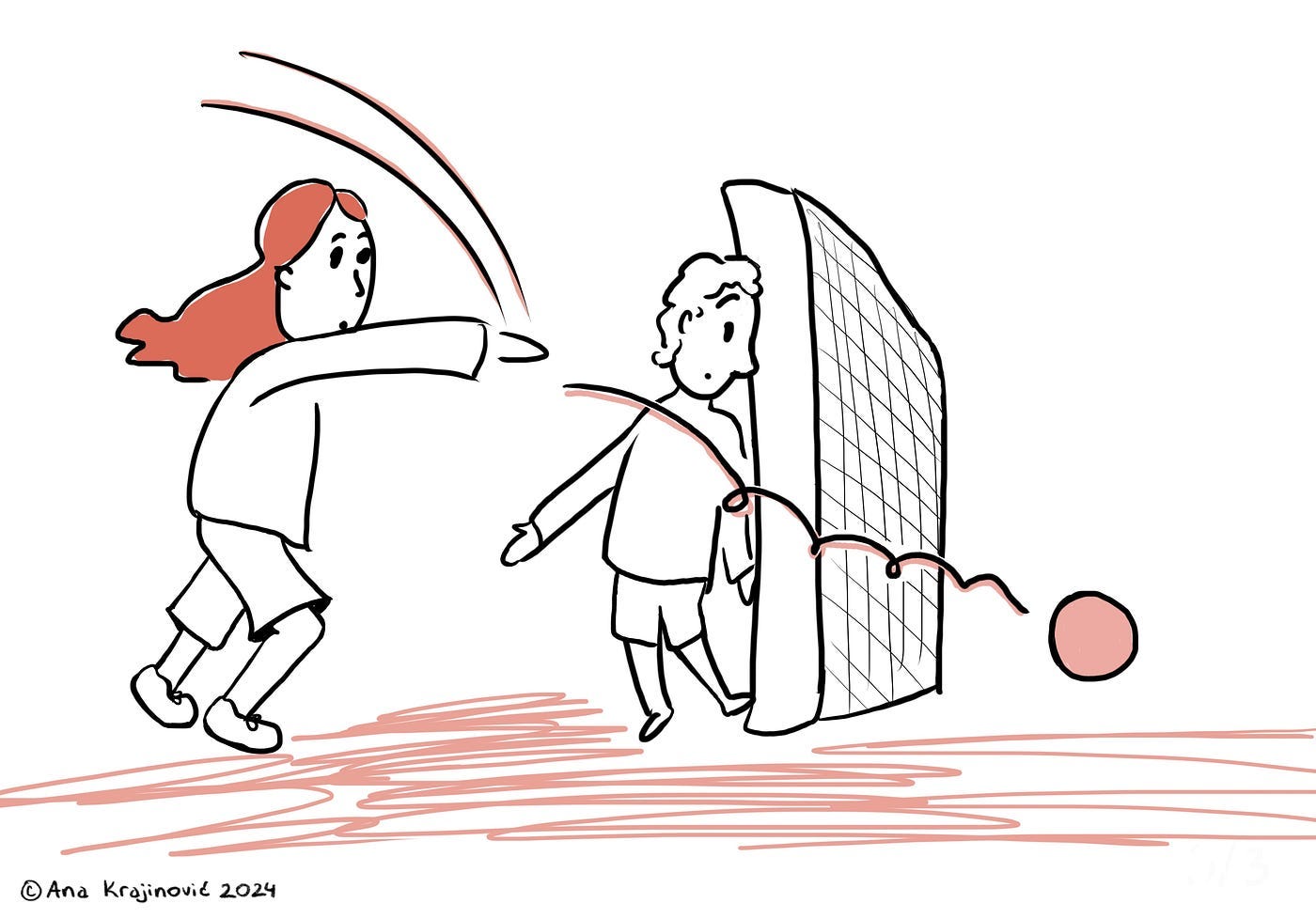

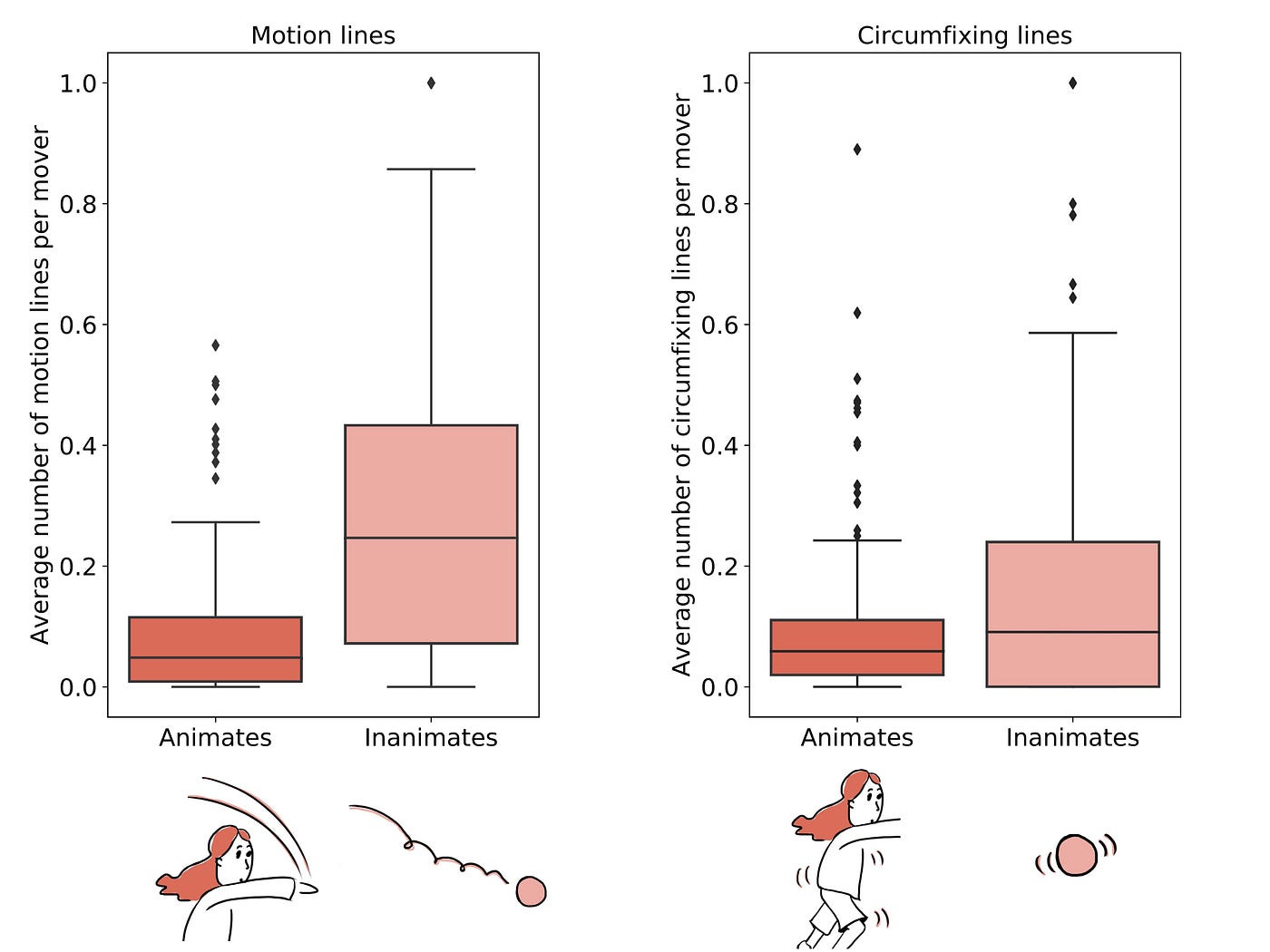

In comics, there are two main types of lines that indicate movement: motion lines and circumfixing lines. Motion lines trail behind the figure and indicate the direction of the movement, while the circumfixing lines are placed around the character and do not provide any information about directionality (Hacımusaoğlu & Cohn, 2023). The two images below exemplify both types.

Comparing the two images above, we can tell that the directionality of the movements is clear with motion lines and completely lost with circumfixing lines. In fact, the last image looks slightly confusing, because the character (animate) and the ball (inanimate) seem to be shaking independently from each other and we are not even sure whether the ball was thrown or not. So, what does that mean for our question about how we perceive animacy?

Motion lines indicate goal-directed movement and according to Opfer (2002), that is crucial for understanding whether something is animate. So, we expect that motion lines might be used differently with animates and inanimates. Different how? In a quantitative way, of course.

We took 331 comics from all over the world and checked whether each character (animate) and object (inanimate) had any lines, motion or circumfixing. We then compare animates and inanimates to see which ones have lines more often.

We expect to find the difference between animates and inanimates only in the case of motion lines because they are goal-directed. When it comes to circumfixing lines, we don’t expect to find any difference between animates and inanimates, because they don’t have any feature that might indicate whether something is animate or inanimate.

What we found

What we found is exactly what we expected: There is a difference between animates and inanimates when it comes to motion lines. Inanimates are more often followed by motion lines than animates. With circumfixing lines, on the other hand, there is no significant difference in how often animates and inanimates are marked by them. The figures below show our results.

The only question now is why are inanimates more marked by goal-directed motion lines? Also, if goal-directed motion is perceived as animate, shouldn’t animates have more motion lines?

The basic idea is that humans have expectations about who moves in a goal-directed way. Here is an explanation of our theory in pictures.

Explanation for why animate are less marked by motion lines:

Explanation for why inanimates are more marked by motion lines:

Inanimates moving in a goal-directed way defy our basic expectations about the difference between beings with intentionality and those without it. Since in comics we cannot see the movement as we do in the real world, we use motion lines more often to indicate that inanimates are moving in a goal-directed way, which is unexpected from them. In our study, we call this principle “Mark the unexpected!”.

With this study, we confirmed that humans use goal-directed motion as a cue to determine whether something is animate or not. And we went one step further and discovered that in comics, this leads to the principle of “Mark the unexpected!”. In other words, we depict this goal-directed movement more often with inanimates, which we do not expect to see moving around like animates.

Despite my stubborn attempts at detecting the signs of life in a coral with the naked eye, maybe it’s time I accept my human attention is shaped by the animacy preference and goal-directed movement. Next time, I’ll bring a microscope.

You can read the preprint of our full research paper here, where we also explain how these results connect to different aspects of spoken language and surprisal.

Based on:

Krajinović, Ana, Irmak Hacımusaoğlu, and Neil Cohn (all authors from Tilburg University). 2024. Mark the unexpected! Animacy preference and goal-directed movement in visual language, Ms.

Authors:

Ana Krajinović is a postdoc in the TINTIN project at Tilburg University. She is a linguist, writer, and a comic artist working on how comics connect to language and cognition.

Irmak Hacımusaoğlu is a PhD student in the TINTIN project at Tilburg University. She is a cognitive researcher and doodle artist exploring the representation of motion and time in comics in her research.

Neil Cohn is an Associate Professor at Tilburg University and the head of the TINTIN project. In his research, Neil explores the structure and cognition of drawings and visual narratives, like comics, as well as language and multimodality.

References:

Hacımusaoğlu, I., & Cohn, N. (2023). The meaning of motion lines?: A review of theoretical and empirical research on static depiction of motion. Cognitive Science, 47(11). doi: 10.1111/cogs.13377

New, J., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2007). Category-specific attention for animals reflects ancestral priorities, not expertise. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(42), 16598–16603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703913104

Opfer, J. E. (2002). Identifying living and sentient kinds from dynamic information: The case of goal-directed versus aimless autonomous movement in conceptual change. Cognition, 86(2), 97–122. doi: 10.1016/S0010–0277(02)00171–3