Fieldwork Is a “Hero’s Journey” of Linguistics: What Can You Learn From It?

6 fieldwork steps that lead to great personal and scientific discoveries, told in comics.

LANGUAGE EXPLAINED

6 fieldwork steps that lead to great personal and scientific discoveries, told in comics.

You are sitting in public transport, deep in your thoughts, when you overhear a foreign language. “What language are they speaking in?” you ask yourself. “It sounds a bit like it could be Russian, but not really, I can’t tell…” How many times did you find yourself in this situation?

Now, imagine if someone told you you have to talk to those people and figure out the grammar and the vocabulary of that language by any means you have, without peeking into the teaching materials for that language. This is basically what linguists do when they do fieldwork. Why would we do that? you might ask.

Well, most languages in the world do not have any teaching materials, many also don’t have any grammatical descriptions or dictionaries. There are over 7000 languages in the world and most of them have not been studied enough for such materials to exist. That’s why we do fieldwork — to find out how any one out of those 7000 languages works. However, this type of work also has unintended consequences.

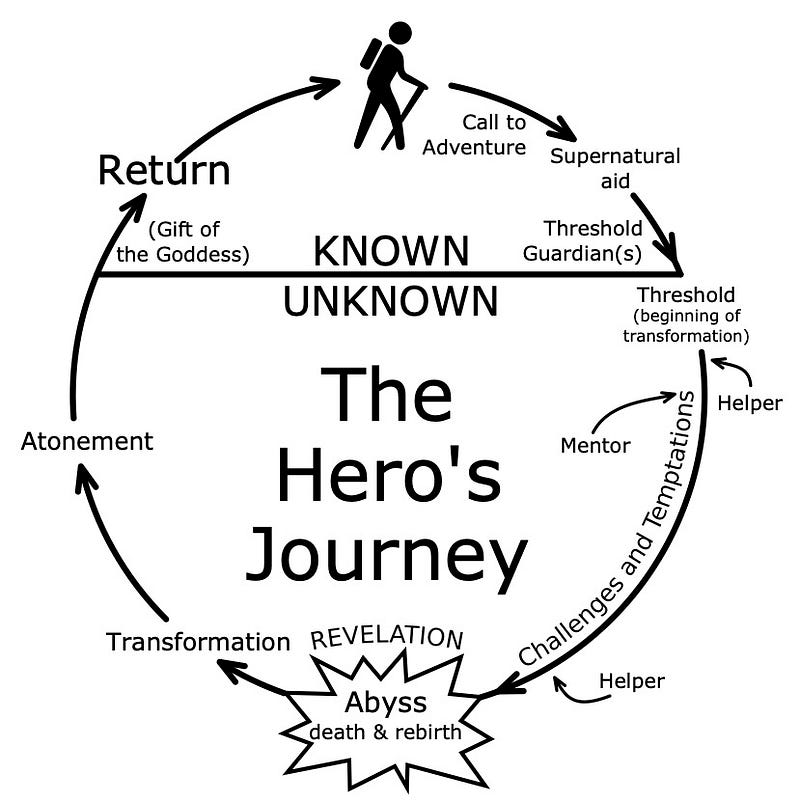

Linguistic fieldwork is utterly transformative. It is not an exaggeration to say that it is a true hero’s journey of linguistics — you know what I mean, the transformation that our heroes in films and books go through, see below.

1. The adventure starts: You discover new languages and new cultures.

Just like in all good stories, the adventure starts with a calling. You just feel like traveling to a distant place and doing fieldwork is something you need to do. The itch to find out what kinds of languages exist out there is just too itchy and you need to scratch it. There is a linguistic mystery and you have to be the one to solve it. I’m running out of metaphors, you get my point, the adventure is calling for you. Believe me, you will know if you get called.

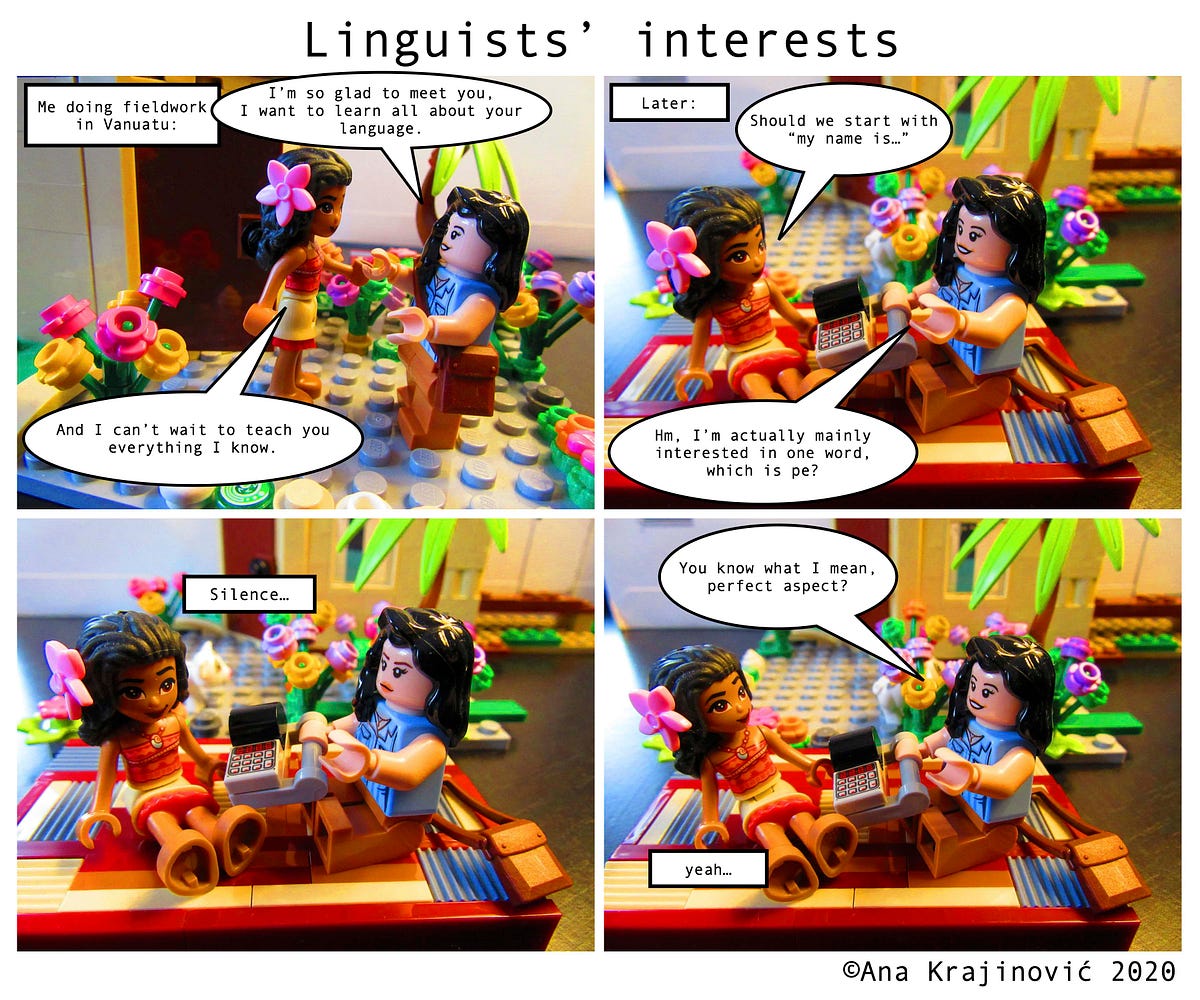

Once you get to your fieldwork site, you are exhilarated. Everything is super exciting and you want to try and learn everything: First, figuring out the language you came to study as a linguist and, second, everything else (food in my case, see comic below). Throughout this article, you will be able to read LEGO comics based on my fieldwork experience. Some parts are slightly exaggerated for humor purposes, but it’s all based on true events.

So, I did linguistic fieldwork for my PhD in Vanuatu, a beautiful small volcanic archipelago in the South Pacific. Being from Europe, you can imagine that visiting a place that far from home, with a completely different climate, was a novel experience, which I wholeheartedly embraced and enjoyed.

2. You discover completely new features of language.

Let’s not forget what set us off on this journey: linguistics! As I said in the beginning, most of us who do fieldwork work with languages that have not been studied much. These are usually languages with a relatively small number of speakers. The language I was studying, Nafsan, has only around 6000 speakers, and there are many languages with much less speakers.

This means that you could be the first linguist ever to find out not only new words in that language but also new grammatical structures that might be rare or little understood in other languages. You are at the very edge of what is known about the languages of the world.

To be perfectly honest, I didn’t find anything “crazy unexpected” in Nafsan, but then again, when you are a linguist, every small detail of grammar is in a way crazy and unexpected. When you are deeply interested in understanding how Nafsan speakers use future tense or perfect (as in present/past perfect in English), every detail that gets you closer to understanding its meaning is exciting and not expected at all. Besides, just the fact that you are one of the only linguists in the world (sometimes you could be the only one) working on that language can feel very special.

For curious linguistic minds, kefi 50 vatu* in the comic above means “will that be 50 vatu”, but it could also be translated as “is that going to be 50 vatu” or “would that be 50 vatu”, or even “is that 50 vatu”. These different interpretations are due to kefi “will/would it be” and that’s why I was so interested in it. I still haven’t fully figured it out, so don’t ask me what translation is the best one.

*Vatu is the currency of Vanuatu.

3. You struggle: You learn how to deal with unpredictable challenges.

Coming out of the honeymoon phase of our adventure, we will inevitably go through struggles. Many struggles can emerge in fieldwork, but the most important one is the one in your head:

You came to this place to do very important work and understand a language previously unknown to you (and most of the academic linguistic community). But soon enough you realize that your academic pursuits are of little use to the speakers of the language you are working with. This makes you realize that, in fact, they are of little use outside of Uni back home too.

And all of this probably started when the first speakers you worked with didn’t understand why you kept insisting on asking them about the future tense and present perfect, etc. They hoped you would work on something fun, maybe you would just learn their language. But no, linguists are mainly interested in details of grammar and lexicon, so they can build theories of language and explain how language works in general. “It is a valid scientific pursuit, but is it enough?” you will start asking.

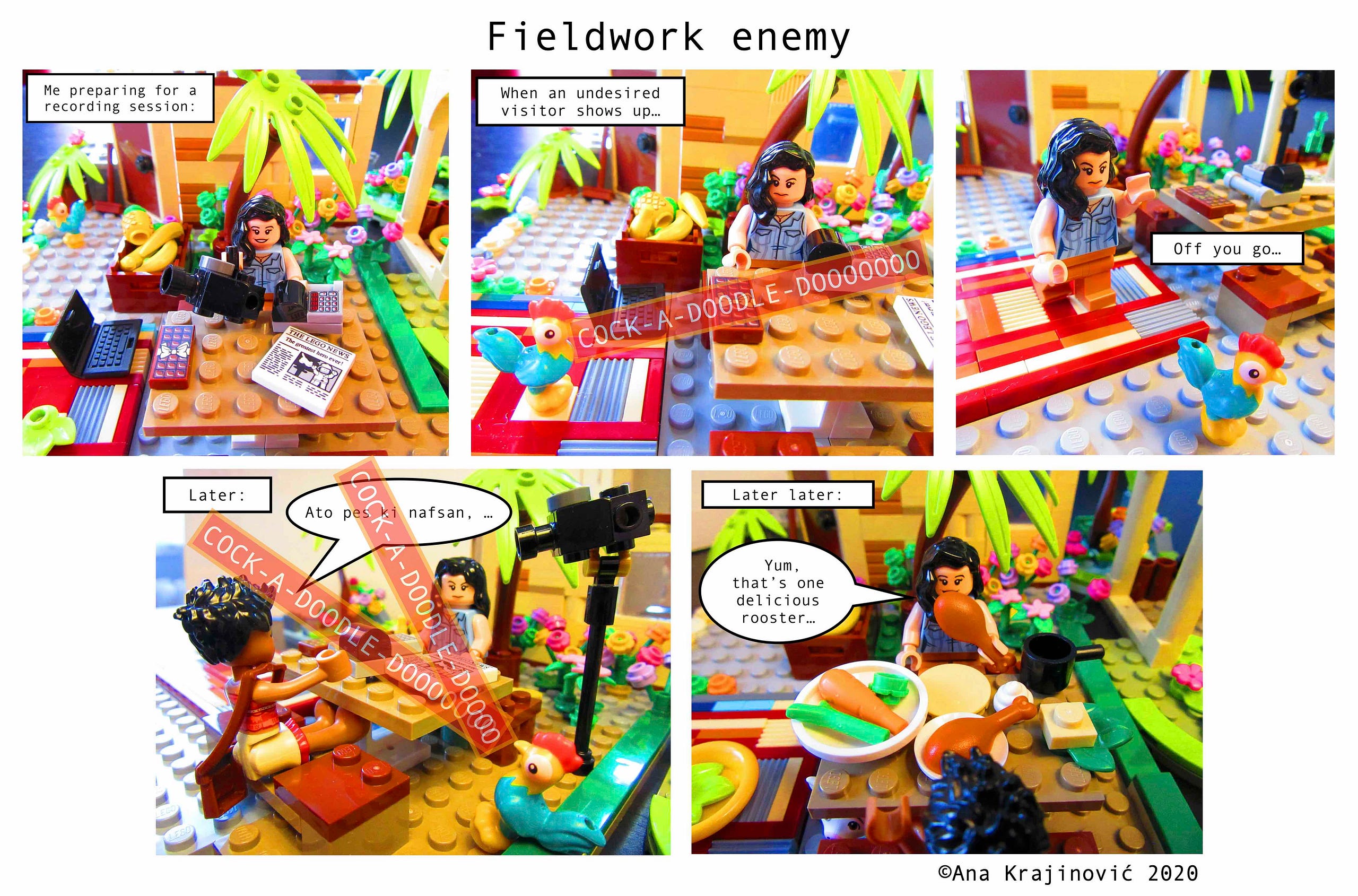

Most of these thoughts though are only in the back of your mind, as you go about the daily struggles of trying to make enough recordings of enough people, so you have enough data for your PhD. In all this mess, you realize that, even when things don’t quite work out, you always find friends who are willing to help out and set you back on track of your research program.

But these thoughts that make you question your linguistic purpose will often resurface and at some point you won’t be able to ignore them anymore:

Why am I doing this? Are these people going to benefit from my work at all? I call myself an expert, but they are experts in their language. Who am I to “work on” their language?

Although this stage is uncomfortable, it is a necessary step to bring you to your growth and rebirth.

4. Rebirth starts: You connect to other people and you learn how to listen to them.

You finally realize that the answer to your struggles has been there all along: Your work is not all about linguistics, it’s about human connection. The purpose of fieldwork is not just your academic work, it is more so about connecting with the people who speak the language you are so interested in.

Once you realize that, you see that the people you have been working with on the language have been helping you in many different ways: from cooking for you to figuring out parts of your research for you! And sometimes getting rid of an annoying noisy rooster that ruins all your recordings…

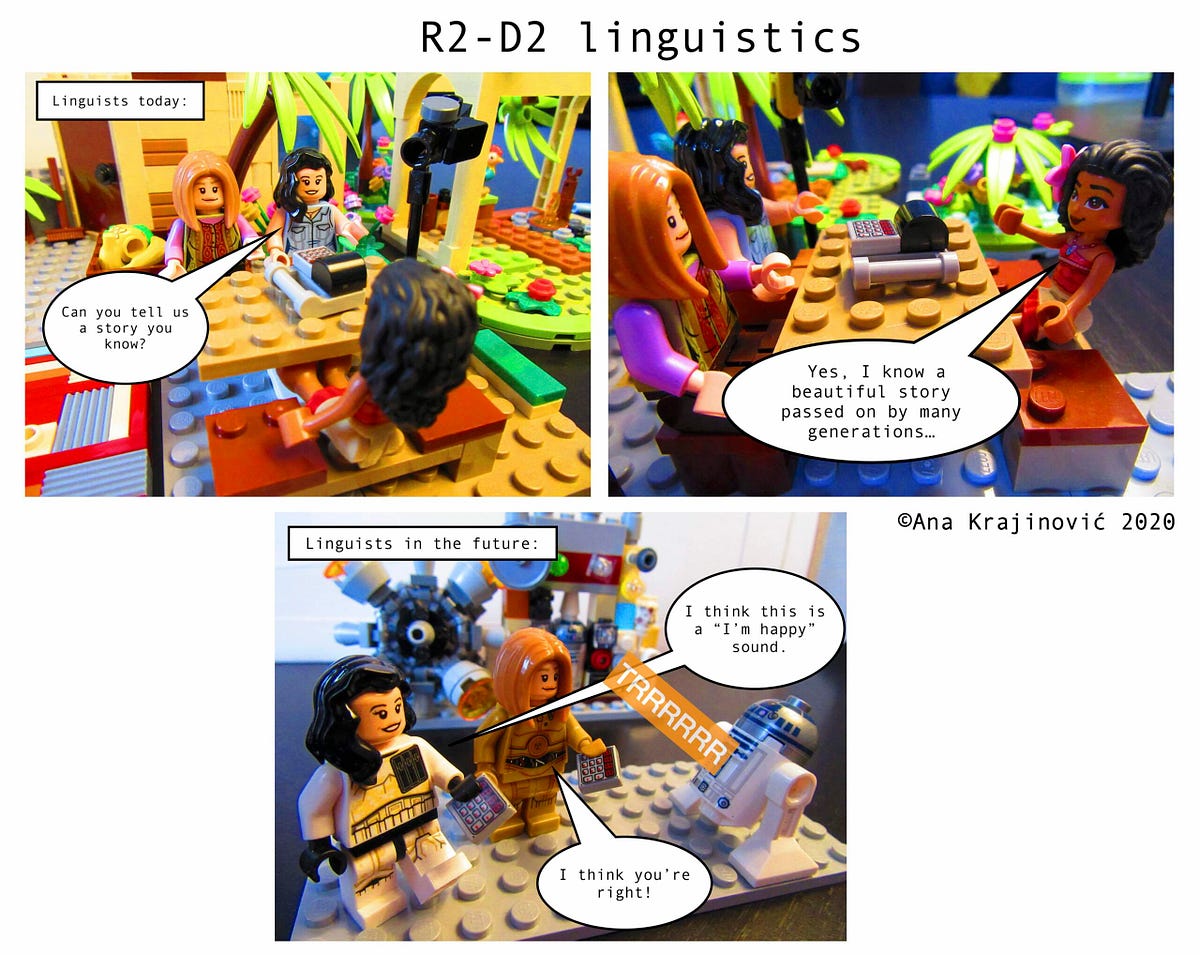

You finally start paying attention more closely to what is happening around you: Maybe the speakers of the language would love it if you could help them create an illustrated book in their language and maybe they have suggestions for how to do it. Maybe your recordings can be useful to them after all. Now you are listening and so you are able to hear what comes next.

5. You start understanding the depth of issues faced by indigenous and endangered languages.

Before you did fieldwork, you already knew that the language you would be working with is endangered and maybe its speakers went through a period of colonization. But you could not have imagined just how profoundly the colonization affected their way of life.

Prior to doing fieldwork, you might have thought about some of the “positive” consequences of colonization, like the (limited) presence of Western medicine, but now you see that there are many more negative social aspects: land being taken and sold, pollution, and capitalism in a society that did quite well without it for so long.

On top of that, the languages of ex-colonizers are still here, occupying the domains of life where indigenous languages could be spoken: in schools, media, and the government. There are many reasons for this and they are all very complex. It’s all very messy, but you finally understand a bit more the way in which it is messy.

UNESCO predicts that by the end of this century, half of the languages currently spoken will have ceased to exist. Fieldworkers are running a race against time, trying to document the linguistic diversity we are still able to attest.

6. Gathering all this knowledge becomes your linguistic and humanistic superpower!

And finally, our linguist hero has made it to the other side. Once you return home, you are ready to use all this knowledge. After publishing your scientific results and actively deciding not to despair in the face of the grim future for endangered languages, you can start educating others about these issues, and become a voice for those who don’t have a voice.

The lessons learned in this hero’s journey are multifaceted. You learned a great deal about the language from an academic linguistic perspective. In a very personal way, you also learned that an experience like fieldwork could never be just an academic enterprise. It involves people and as such, it is first and foremost about people and your connection to them. This knowledge is your superpower.

If you liked this, sign up for our newsletter below.

About the author and editor: Ana Krajinović

I am a postdoctoral researcher at the Heinrich Heine University of Düsseldorf. In 2020 I completed my PhD in linguistics at Humboldt University of Berlin and the University of Melbourne on Nafsan, an Oceanic language spoken in Vanuatu. During the pandemic, I started creating short comic strips about linguistics and fieldwork. My website: https://anakrajinovic.com.